Learning the many potential symptoms and signs of this rare condition could be vital to your patient's timely care.

As a doctor, you know that a trip to your office can be a vulnerable time for your patients. But for people with rare conditions like tuberous sclerosis complex, the healthcare system can feel like a constant battle. Imagine having to explain your condition and its effects repeatedly to every healthcare professional you encounter. Here’s what you need to know about this rare condition and how to manage lung and other complications in your patients.

What is tuberous sclerosis complex?

Tuberous sclerosis is a genetic disorder caused by mutations in the tumour-suppressor genes TSC1 and TSC2, located on chromosomes 9 and 16, respectively.

The estimated incidence is approximately one in 6000 live births. While tuberous sclerosis can sometimes be inherited, in about two-thirds of cases it occurs spontaneously. It is an autosomal dominant disorder; so there is a 50% chance of an affected person passing the mutation on to their child.

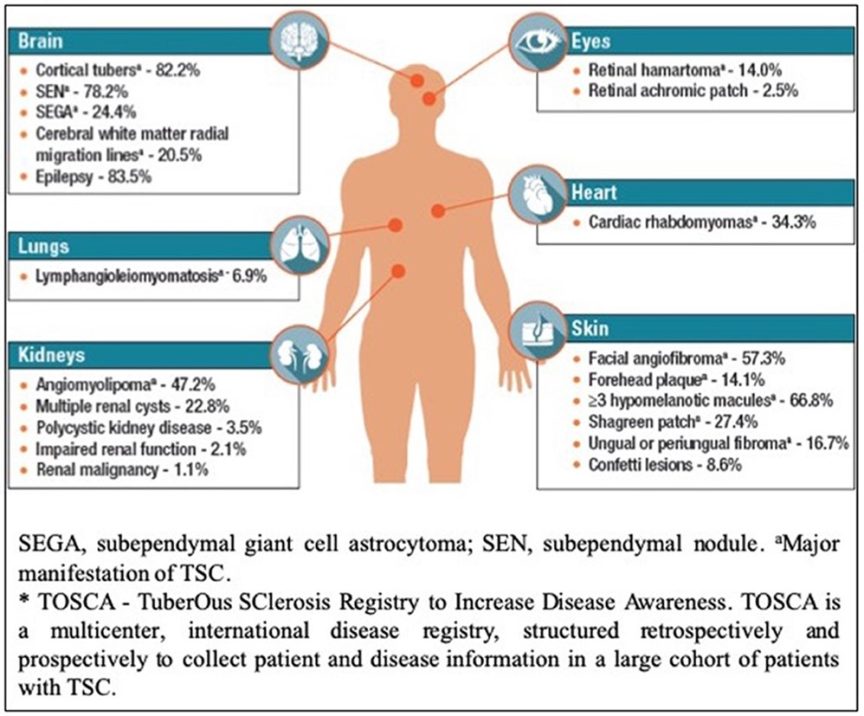

Pathogenic mutations in TSC1 or TSC2 cause over-activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway, leading to the growth of benign tumours (also known as hamartomas) in various organs, including the brain, kidneys, skin, heart, lungs and bones. These hamartomas are the clinical hallmarks of tuberous sclerosis.1

Tuberous sclerosis is a multisystem disorder that can affect almost any organ in the body. Skin lesions such as facial angiofibromas, hypomelanotic macules (also known as ash leaf patches), shagreen patches (flesh coloured naevi with an orange-peel texture, usually found on the lower back), forehead fibrous plaques, and periungual fibromas are common. However, lesions in the central nervous, renal and pulmonary systems can cause more serious morbidity.

Epilepsy, often secondary to cortical and subcortical tubers, is a common presenting symptom and an ongoing problem in tuberous sclerosis.

Most patients with this condition experience seizures during infancy, and many continue to suffer from intractable epilepsy throughout life.

Subependymal giant cell astrocytomas which are slow-growing benign tumours, are seen in 5-20% of individuals and can cause clinical problems by blocking cerebrospinal fluid pathways within the ventricular system, leading to obstructive hydrocephalus.

Over 80% of patients with tuberous sclerosis have kidney angiomyolipomas, which can bleed and cause life-threatening haemorrhages or destruction of viable renal tissue, ultimately leading to renal failure.

Pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis, which occurs almost exclusively in female patients, can cause progressive shortness of breath, recurrent pneumothorax and deterioration in lung function.2

Neurological and neuropsychiatric symptoms are highly prevalent in patients with tuberous sclerosis, affecting approximately 90% of cases and presenting at different stages of development. Tuberous sclerosis-associated neuropsychiatric disorder contributes significantly to the overall burden of the disease, as noted by multiple studies.

Despite advancements in the identification and treatment of physical features associated with tuberous sclerosis, including subependymal giant cell astrocytomas, angiomyolipomas, and epilepsy, neuropsychiatric manifestations still often go unrecognised and untreated.3

It is important to note that tuberous sclerosis can present with a wide range of symptoms and severity. Some people are severely affected whereas others may not even know they have it. Diagnosis requires input from specialists in neurology, dermatology, nephrology, and genetics, as well as neuropsychiatric input.

Prompt referral to the appropriate specialists and early diagnosis and treatment can significantly improve outcomes for individuals with tuberous sclerosis.

Diagnosing tuberous sclerosis complex

Tuberous sclerosis may be diagnosed by a combination of clinical features and genetic testing. The majority of patients are diagnosed using a clinical diagnostic criteria and genetic testing, although increasingly done, is not usually required for a diagnosis.4

The symptoms of tuberous sclerosis can vary depending on the organs affected, and the stage of life at which symptoms present, making it a difficult condition to diagnose.

In a study of 73 patients, one in four had a missed diagnosis after the first presentation of symptoms. Seizures, being one of the most common presenting symptoms, and a major risk factor for poor cognitive development, were also one of the most commonly missed.2

Other signs include developmental delay, and unique skin abnormalities like hypomelanotic macules and facial angiofibromas (which may sometimes be mistaken for facial acne).

To definitively diagnose tuberous sclerosis, a person must have either two major features or one major feature with two minor features. However, a combination of the two major clinical features, lymphangioleiomyomatosis and angiomyolipomas without any other features doesn’t meet the criteria for a definite diagnosis because they can occur together in sporadic disease that is not tuberous sclerosis.

A definite diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis can be made if a pathogenic mutation is present in either the TSC1 or TSC2 genes. A pathogenic mutation is a genetic variation that prevents the production of TSC1 or TSC2 protein. While some mutations that allow protein production can still cause the disease and lead to a definite diagnosis, others should be approached with caution.4

This is because not all mutations in these genes will completely prevent the production of TSC1 or TSC2 protein. Some mutations may still allow some protein production but be dysfunctional, or could contribute to the development of the disease.

However, tuberous sclerosis is mainly diagnosed on clinical criteria as genetic testing requires geneticist input and is expensive.

Table 1 (below) outlines the diagnostic criteria for tuberous sclerosis complex.4

| BODY SYSTEM | MAJOR FEATURES | MINOR FEATURES |

| Skin | Angiofibromas (3 or more) or forehead plaqueHypomelanotic Macules/Ash Leaf Patches (3 or more, at least 5mm in diameter)Shagreen Patch | “Confetti” skin lesions |

| Nails and Teeth | Ungual fibromas (2 or more) | Dental enamel pits (more than 3)Intraoral fibromas (2 or more) |

| Eyes | Multiple retinal hamartomas | Retinal achromic patch |

| Renal System | Angiomyolipomas (2 or more) | Multiple renal cysts |

| Brain | Multiple cortical tubers and/or radial migration linesSubependymal nodules (2 or more)Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma(s) | |

| Cardiac System | Cardiac rhabdomyoma | |

| Respiratory System | Lymphangioleiomyomatosis | |

| Other | Non-renal hamartomas Sclerotic Bone Lesions |

FIG 1: Body systems commonly affected by tuberous sclerosis complex.5

The clinical presentation of tuberous sclerosis varies depending on the individual’s developmental stage. Table 2 (below) outlines common presentations at each age; this is by no means exhaustive:

| PRENATAL | INFANCY/CHILDHOOD | PUBERTY/ADOLESCENT | ADULT |

| Cardiac rhabdomyomas, cortical tubers | Infantile spasms, seizures, hypopigmented macules, developmental delay, angiofibromas, cardiac rhadomyomas, retinal hamartoma | Ungual fibromas, facial angiofibromas, new onset seizures, angiomyolipomas, neuropsychiatric symptoms | Lymphangioleiomyomatosis, angiomyolipomas, bone lesions, skin lesions |

Tuberous sclerosis complex can be difficult to diagnose due to the variety of symptoms and signs that may not immediately suggest the disorder. Patients may experience delays in receiving a correct diagnosis or may be misdiagnosed with another condition. To ensure early diagnosis, healthcare providers across multiple specialties should be familiar with the many potential symptoms and signs of tuberous sclerosis. Early diagnosis enables prompt evaluation, ongoing symptom management, family planning, genetic counselling and improved outcomes.2

Genetic/prenatal/pre-implantation evaluation

To ensure the most effective approach to addressing genetic risks and discussing the availability of prenatal or preimplantation genetic testing, it is advisable to refer patients with tuberous sclerosis to a clinical geneticist for genetic counselling prior to conception.

IVF and preimplantation genetic testing for tuberous sclerosis can be undertaken however these interventions carry a significant cost to the patient and necessitate a referral to a fertility specialist.

Invasive prenatal testing such as amniocentisis and chorionic villus sampling can detect tuberous sclerosis in-utero, however these procedures carry inherent risk to the developing foetus. There is also a risk of detecting confined placental mosaicism during these procedures (where there is genetic variation or abnormality present in the cells of the placenta, but not in the cells of the developing foetus).

Cardiac rhabdomyomas can be detected in-utero during the 3rd trimester via ultrasound and fetal ECG. If fetal ultrasound examination reveals cardiac lesions consistent with rhabdomyoma and there is no known family history of TSC, the risk of the fetus having tuberous sclerosis complex is estimated to be 75%-80%.7

Genetic counselling and testing plays a crucial role in ensuring informed decision-making and appropriate management for individuals with tuberous sclerosis.

Treatment/Management

There is currently no cure for tuberous sclerosis, but there are treatments available to manage the symptoms of the disease. Treatment is primarily focused on reducing the morbidity burden of the condition and improving quality of life. Most individuals with tuberous sclerosis will have a normal lifespan, however the research on life expectancy in tuberous sclerosis is limited.

Up to 90% of patients with tuberous sclerosis experience seizures and these often present within the first 12 months of life in the form of infantile spasms. They can be subtle and easily missed, so being aware of the presentation and asking the parents to take a video if there is suspicion is helpful.

Vigabatrin, either after seizure onset or prophylactically is considered a first-line treatment for tuberous sclerosis-associated epilepsy.8 Research into preventive intervention in infants with tuberous sclerosis (beginning treatment with anti-epileptic medications and/or mTOR inhibitors prior to seizures occurring) is ongoing and early evidence shows promising results.9

In patients with refractory epilepsy who are surgical candidates, surgical intervention may also be considered.10 This is mainly done out of the tertiary paediatric public hospitals in Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane.

A growing body of evidence suggests that mTOR inhibitors such as sirolimus and everolimus are safe and effective treatments for many manifestations of tuberous sclerosis, including angiomyolipomas and lymphangioleiomyomatosis.11 Dosing, titration and prescribing of mTOR inhibitors is coordinated by the main specialist, usually a neurologist or nephrologist.

Skin lesions can be treated with a compounded topical rapamycin cream, prescribed by a dermatologist who is familiar with treating tuberous sclerosis.

Tuberous sclerosis-associated neuropsychiatric disorder (TAND) can include behavioural, psychiatric, intellectual, academic, neuropsychological and psychosocial manifestations. Despite affecting up to 90% of individuals with tuberous sclerosis at some point in their lives, tuberous sclerosis-associated neuropsychiatric disorder is often overlooked and under-researched, leading to inadequate assessment and treatment.

Regularly screening for tuberous sclerosis-associated neuropsychiatric disorder and referring patients to multidisciplinary health professions if there is suspicion (psychiatry, psychology, occupational therapy, speech pathology, etc) is important in improving patient outcomes.

Regular surveillance is critical in treating and managing tuberous sclerosis. You can download and view the tuberous sclerosis surveillance and management guidelines on this page.

Table 3 details the surveillance guidelines:4

| ORGAN | TEST | NEW DIAGNOSIS OR SUSPICION OF TSC | EXISTING TSC |

| BRAIN | MRI Brain +/- gadolinium | Yes | Every 1-3 years up to 25 years old. Periodically in adults with childhood SEGAs |

| EEG | Yes. If abnormal, 24hr video EEG | Routine EEG is suggested every six weeks in asymptomatic infants <12 months old and every three months in infants 12-24 months of age. Video EEG if seizure occurrence is unclear or new behavioural or neurological symptoms are present | |

| TAND checklist | Yes | At least annually | |

| Comprehensive evaluation for TAND | If TAND checklist indicates clinical need | At key developmental stages/ages: 0-3 years, 3-6 years, 6-9 years, 12-16 years, 28-35 years and as needed thereafter | |

| Counsel parents of infants | Educate parents to recognise seizures | ||

| EYES | Comprehensive eye exam with dilated fundoscopy | Yes | Annually if lesions/symptoms at baseline |

| SKIN/TEETH | Detailed skin exam | Yes | Annually |

| Detailed dental exam | Yes | Six monthly | |

| Panoramic radiographs of teeth | Age seven or older | At age seven if not done previously | |

| HEART | Fetal echocardiography | If cardiac rhabdomyomas identified by prenatal ultrasound | |

| Echocardiogram | Yes, especially in children under three years old | Every 1-3 years if rhabdomyoma present, more frequently if symptomatic | |

| Electrocardiogram | Yes | Every 3-5 years; more frequently if symptomatic | |

| KIDNEYS | Blood pressure | Yes | Annually |

| Abdominal MRI (in Australia ultrasound of the kidneys is the common practice) | Yes | Every 1-3 years | |

| LUNGS | Clinical screening for LAM symptoms (evaluate for chronic cough, chest pain, breathing difficulty) | Yes | At each clinic visit |

| Pulmonary function test and 6-min walk test | In females 18 years or older; in adult males if symptomatic | Annually if lung cysts detected by high resolution computed tomography (HCRT) | |

| High resolution computed tomography (HCRT) of chest | In females 18 years or older; in adult males if symptomatic | Every 2-3 years if lung cysts detected, otherwise every 5-10 years | |

| Counsel on risks of smoking and oestrogen use | In adolescent and adult females | At each clinic visit for individuals at risk of LAM | |

| GENETICS | Genetics consult | Obtain 3 generation family history | Refer to geneticist for genetic testing for TSC and counselling if not done previously in individuals of reproductive age |

Tuberous sclerosis complex is a rare genetic disorder that can affect multiple organs and cause significant morbidity for patients and their families. Diagnosis is based on clinical criteria, and ideally patients should be referred to a multidisciplinary team of specialists for management wherever possible.

Although there is no cure for tuberous sclerosis, treatments are available to manage the symptoms. Ongoing research aims to identify new therapies and improve our understanding of the pathogenesis of tuberous sclerosis.

The clinical course of tuberous sclerosis can be highly variable, and the prognosis may be uncertain.

Follow-up care requires a comprehensive evaluation, where possible in specialised clinics or treatment centres. Tuberous sclerosis complex can be overwhelming for patients and their families, and orientation and counselling play a critical role in helping them manage the condition and its impact on their lives.

Clinicians can make a significant difference in the lives of tuberous sclerosis patients by staying informed about the latest developments in diagnosis and treatment of tuberous sclerosis and advocating for proper care and surveillance.

Katrina Watt is the Registered Nurse for Tuberous Sclerosis Australia (TSA), the only not-for-profit organisation supporting people with TSC in Australia. She provides nursing care, support, and information to people with TSC and their families and carers, as well as other health professionals.

References:

1. Amin, S., Lux, A., Calder, N., Laugharne, M., Osborne, J., & O’callaghan, F. (2017). Causes of mortality in individuals with tuberous sclerosis complex. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 59(6), 612–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.13352

2. Staley, B. A., Vail, E. A., & Thiele, E. A. (2011). Tuberous Sclerosis Complex: Diagnostic Challenges, Presenting Symptoms, and Commonly Missed Signs. Pediatrics, 127(1), e117–e125. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-0192

3. de Vries, P. J., Wilde, L., de Vries, M. C., Moavero, R., Pearson, D. A., & Curatolo, P. (2018). A clinical update on tuberous sclerosis complex-associated neuropsychiatric disorders (TAND). American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics, 178(3), 309–320. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.c.31637

4. Northrup, H., Aronow, M. E., Bebin, E. M., Bissler, J., Darling, T. N., de Vries, P. J., Frost, M. D., Fuchs, Z., Gosnell, E. S., Gupta, N., Jansen, A. C., Jó?wiak, S., Kingswood, J. C., Knilans, T. K., McCormack, F. X., Pounders, A., Roberds, S. L., Rodriguez-Buritica, D. F., Roth, J., … International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group. (2021). Updated International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Diagnostic Criteria and Surveillance and Management Recommendations. Pediatric Neurology, 123, 50–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2021.07.011

5. Annear, N. M. P., Appleton, R. E., Bassi, Z., Bhatt, R., Bolton, P. F., Crawford, P., Crowe, A., Tossi, M., Elmslie, F., Finlay, E., Gale, D. P., Henderson, A., Jones, E. A., Johnson, S. R., Joss, S., Kerecuk, L., Lipkin, G., Morrison, P. J., O’Callaghan, F. J., … Kingswood, J. C. (2019). Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC): Expert Recommendations for Provision of Coordinated Care. Frontiers in Neurology, 10. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2019.01116

6. Ma—Tuberous sclerosis complex.pdf. (n.d.). Retrieved June 21, 2023, from http://www.epilepsienrs.com/docs/Tuberous-Sclerosis-Complex.pdf.

7. Northrup, H., & Krueger, D. A. (2013). Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Diagnostic Criteria Update: Recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatric Neurology, 49(4), 243–254.

8. Wang, S., & Fallah, A. (2014). Optimal management of seizures associated with tuberous sclerosis complex: Current and emerging options. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 10, 2021–2030. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S51789

9. Wang, X., Ding, Y., Zhou, Y., Yu, L., Zhou, S., Wang, Y., & Wang, J. (2022). Prenatal diagnosis and intervention improve developmental outcomes and epilepsy prognosis in children with tuberous sclerosis complex. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 64(10), 1230–1236. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.15265

10. Pearsson, K., Compagno-Strandberg, M., Eklund, E. A., Rask, O., & Källén, K. (2022). Satisfaction and seizure outcomes of epilepsy surgery in tuberous sclerosis: A Swedish population-based long-term follow-up study. Seizure, 103, 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seizure.2022.10.011

11. Śmiałek, D., Jóźwiak, S., & Kotulska, K. (2023). Safety of Sirolimus in Patients with Tuberous Sclerosis Complex under Two Years of Age—A Bicenter Retrospective Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12010365

12. Diagnostic Criteria. (n.d.). Tuberous Sclerosis Australia. Retrieved May 15, 2023, from https://tsa.org.au/information/diagnostic-criteria/