This biomarker is also associated with more exacerbations, according to an analysis in The Lancet.

High blood eosinophil counts indicate better response to maintenance therapy in adults with mild asthma, an analysis has shown.

Just as with severe asthma, a biomarker predictive of treatment response and risk of exacerbations in mild asthma would be useful to stratify patients, especially when some patients with mild and infrequent symptoms struggle to commit to daily treatment.

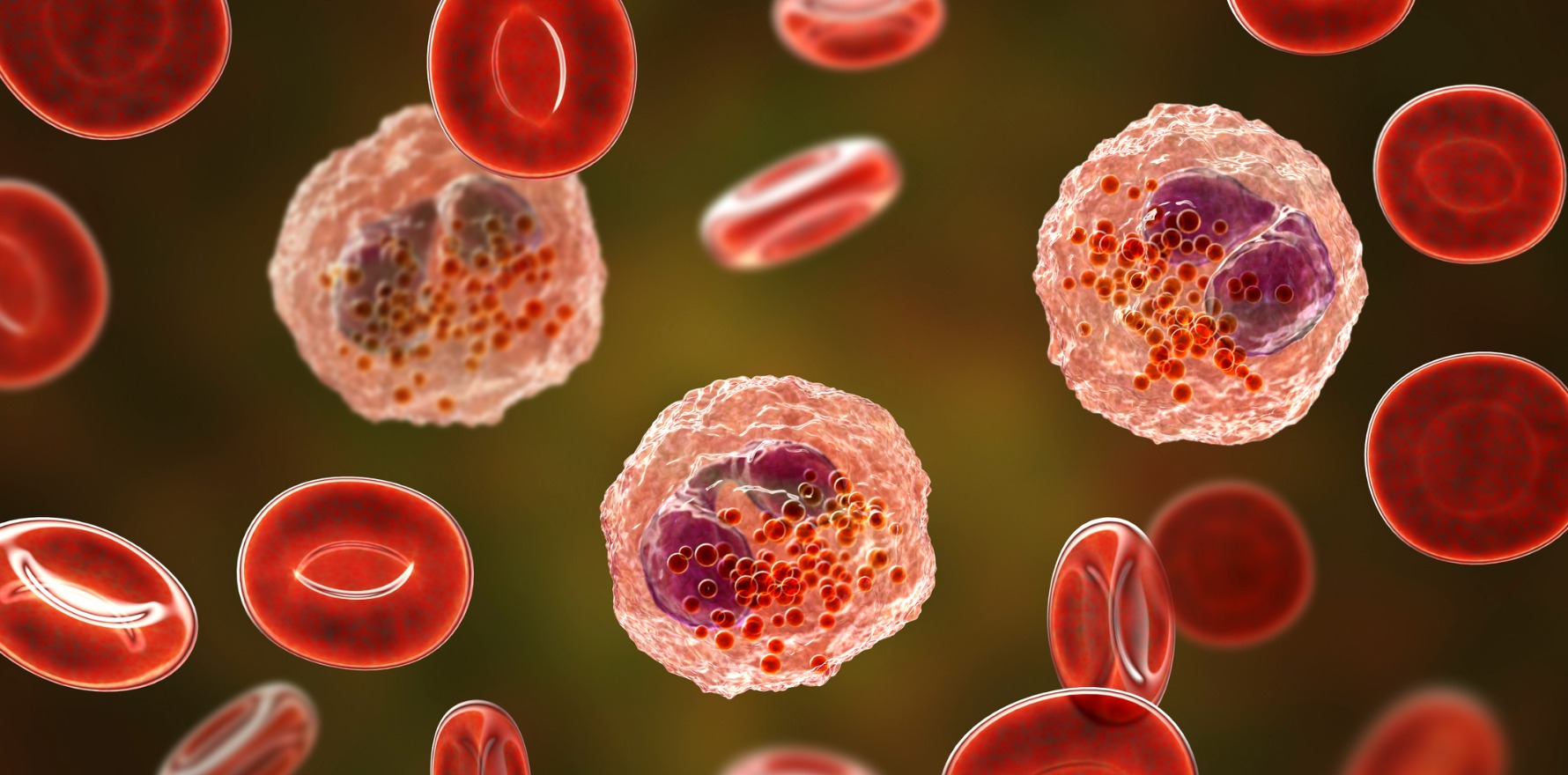

Measuring blood eosinophil counts is common practice in the management and treatment of severe asthma, used to identify patients with a higher risk of exacerbations and those most likely to benefit from an inhaled corticosteroid or biologic therapy.

The analysis of more than 650 patients across 16 clinical trial units showed that the association also holds true in patients with mild asthma: patients with elevated blood eosinophil counts experienced more exacerbations and were more likely to benefit from regular inhaled budesonide (plus SABA as needed) than patients with low counts.

Last year the Global Initiative for Asthma stopped recommending treatment of asthma in adolescents and adults with SABA alone for safety reasons. Instead, people with intermittent or mild asthma should take either a daily low-dose ICS or use an inhaled combination therapy as needed.

The new Australian Asthma Handbook launched last week similarly says ICS are the most effective preventer medicine for adults, that most adults with asthma benefit from ICS and that benefits can be achieved at low doses. Only the “few” patients with symptoms less than twice a month are recommended for as-needed SABA alone.

The latest study, published in The Lancet, was a prespecified secondary subgroup analysis of a 12-month randomised controlled trial of different treatment regimens for adults with mild asthma published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2019.

In the biomarker analysis, patients that had been randomised to either as-needed salbutamol or low-dose ICS, twice daily or as needed, were grouped according to their biomarker status at baseline and the rate of exacerbations resulting in urgent medical care compared.

Two biomarkers were assessed: blood eosinophil counts and nitric oxide. Only eosinophil counts showed an association with outcome and treatment response in adults with mild asthma.

Increased blood eosinophil counts were associated with greater risk of exacerbations: prior to randomisation, patients with mid-to-high baseline blood eosinophil counts were almost three times as likely to have ever had an asthma exacerbation requiring hospital admission than those with low blood eosinophil counts.

Regular treatment with budesonide plus as-needed salbutamol was also more effective than as-needed salbutamol alone at preventing exacerbations among patients with high blood eosinophil counts compared to those with lower counts.

Neither biomarker was predictive of benefit from as-needed combination therapy (budesonide-formoterol).

Professor John Upham, a respiratory physician at the Princess Alexandra Hospital in Brisbane, said the findings were useful and important, with the potential to change clinical practice, in line with current asthma guidelines.

He said blood eosinophil counts should help doctors when making treatment decisions, particularly if they are concerned about suboptimal treatment with an as-needed treatment regime.

“For doctors who are unsure whether to prescribe regular or as-needed ICS [this study shows that] measuring the blood eosinophil count can help make that decision,” he said.

“It can identify who should be on regular treatment as opposed to those who can get away with intermittent treatment.”