Providing cultural safety starts with allowing others to define what it looks like.

I recently took part in a one-day Cultural Safety in Clinical Practice course run by the Australian Indigenous Doctors’ Association (AIDA).

The aim was to help extend the participants’ knowledge about Torres Strait Islander and Aboriginal history and culture, and how attitudes and values can influence perceptions, assumptions, and behaviours in a clinical setting.

The gap in healthcare outcomes between ATSI and other Australians is a travesty, and AIDA maintains that the gap is directly linked to cultural safety and the cultural intelligence quotient (CQ) of clinicians and medical administrators. CQ, a measure like emotional intelligence quotient (EQ), is about addressing our conscious and unconscious biases at both an individual, political, and systemic level.

The experience brought me several epiphanies. Most hospitals and bricks and mortar healthcare settings are not fit for the purpose of delivering medical care to our First Nations people. However, I also identified another barrier to Closing the Gap.

Richard Branson once said “Clients do not come first. Employees come first. If you take care of your employees, they will take care of the clients.” Our medical workforce, it appears to me, is now increasingly multicultural and more so as you move into regional, rural, and remote locations. Therefore, many within the medical workforce experience real issues with regards their own cultural safety.

I have some skin in the game by virtue of being a first-generation Australian, a doctor delivering care to Indigenous people, and having spent time as a patient myself. While there are obvious differences of degree, even a white man can experience the disconcerting effects of a lack of CQ.

My Christian name is Cornelius, for which the Dutch diminutive is Kees (which rhymes with days). I attended primary school in Lae, New Guinea. The Australian expat teachers there found Kees way too burdensome and decided that Keith was the easier option for them.

I then attended Marist Brothers boarding school in Sydney, where the chaplain was Monsignor Cornelius Duffy. The now departed Irish Monsignor, on discovering that we “shared” a name, offered me the option to be called either Con or Neil. My identity was again hijacked by an “educated” person with low CQ.

These names and diminutives were foreign to me. How could a chaplain responsible for pastoral care not understand that I simply desired to be known by the name that my parents called me?

Furthermore, because I was in fact neither a Keith nor a Neil, my classmates determined that I must be a “wog”. When I asked what a wog was, they said anyone who is not of Anglo-Saxon ancestry, betraying their abysmal ignorance of European history.

I had a fondness for hot Milano salami, which was social suicide in Australia during the mid-1960s. But I was an athletic white male with blue eyes and blond hair. Needless to say, I was lucky in comparison to how my brown-skinned, brown-eyed, black-haired brothers and sisters fared.

So what is CQ?

CQ is about being prepared to go on a journey to understand personal differences which are culturally derived, being sensitive to those differences through self-exploration, and doing your best to afford cultural safety via ongoing personal critical reflection.

Importantly, it is the recognition that cultural safety is defined by those receiving your interactions or care. How will you know if you miss the mark? The answer is implicit. Don’t expect the spoken word. Those who feel culturally unsafe will become demoralised and may shut down or walk away.

Health economists are now the people who save or prolong lives at a population level. Sadly, their levers are economics, which demands the elimination of waste. For them, variation is waste and therefore economically inefficient and costly. This concept is attributed to the Continuous Improvement Guru W. Edwards Deming, whose intention was that inappropriate variation is costly.

Alas, one-size-fits-all approaches to healthcare create systems that favour the privileged dominant groups and disadvantage cultural minorities. Standardised care assumes the existence of a standardised patient, an anachronistic but still not extinct generalisation.

Standardised person-centred care is an oxymoron. The truth is that one size fits no one, and that there is a link between cultural safety and clinical safety.

Far from power

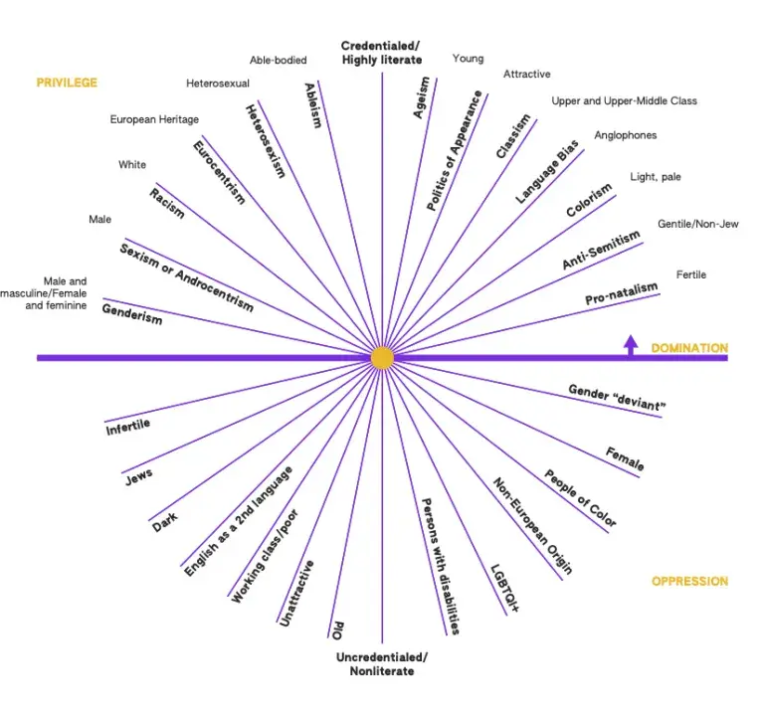

As doctors we enjoy many privileges. We have access to tangible and intangible benefits and power that are denied to many others. If you have never done so, I suggest you reflect on the Wheel of Power and Privilege. It aims to provide a stark reminder of what “marginalisation” means in a cultural and subcultural sense. The further you are from power, the more ignored and unimportant you may feel.

Caption: Wheel of Power and Privilege – based on the Duckworth Wheel

Privilege is a package of unearned assets that we can cash in each day. The question is: should we use these assets on ourselves or others? I suggest we could use these assets to make our work environments culturally safer places.

Sir William Osler said: “The good physician treats the disease; the great physician treats the patient who has the disease.” A failure to attempt to understand and respect patient context is a failure to treat optimally.

This link between CQ and clinical care needs to be showcased. Providing cultural safety ought to be an essential competency of doctors; not having an anti-racist anti-stigma skill set should be regarded as professional negligence.

The terms you’ll find in CQ frameworks – high versus low power distance, task versus relationship focus, high versus low context, uncertainty avoidance and individualism versus collectivism – do not even exist in the mainstream medical lexicon.

(By the way, those frameworks would have been gobbledygook to me six months ago. I was introduced to them at a CQ workshop during the Asia Pacific Symposium on Medical Education.)

Evidence-based medicine has shifted medical curricula towards delivering better evidence-based medical care. In 1996, the CanMEDS Framework (Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada) identified that medical expertise comprised broader domains such as advocate, communicator and collaborator.

That reasoning has now spread globally. It is not yet fully embedded, yet some medical schools such as Stanford have put CQ into their curriculum, considering it a vital component of medical competency.

The drive for evidence-based medicine has been dominated by quantitative interventionist studies. It’s time to change tack and include qualitative outcome measures that focus on the art and humanities of medicine.

Mixing doctors and medical students from all over the world without facilitating CQ impacts on the patient experience. The hidden curriculum’s norms are largely communicated via culture, and culture eats strategy for breakfast. It similarly eats away at clinical outcomes. We must and can do better at addressing our own toxic culture within our profession.

We non-Indigenous Australian doctors need to get our own house in order before we can make it better for our First Nations patients. We have much to gain and nothing to fear from other cultures.

Associate Professor Kees Nydam was at various times an emergency physician and ED director in Wollongong, Campbeltown and Bundaberg. He continues to work as a senior specialist in addiction medicine and to teach medical students attending the University of Queensland Rural Clinical School. He is also a poet and songwriter.