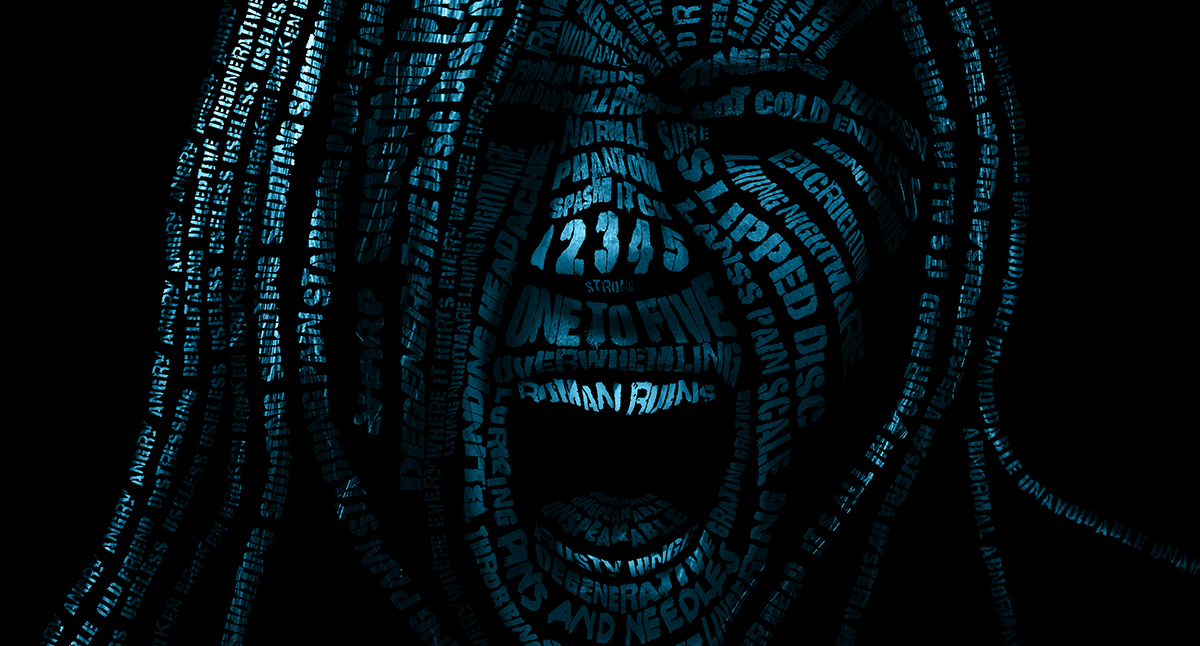

The phrases we use can directly affect a person’s experience of pain.

Many years ago, Professor Lorimer Moseley, now a pain scientist and foundation chair in Physiotherapy at the University of South Australia, was a practising physiotherapist at an Adelaide clinic.

One day, he stepped out into the waiting room to call his next patient.

“Call me Roman,” the man introduced himself to Professor Moseley. That name didn’t match Professor Moseley’s records, so he asked the patient if that was his second name.

“It’s my nickname,” said the man, “Roman ruins.”

Professor Moseley was intrigued. How did he get the nickname?

“Wait until you see my X-ray,” the man said.

Some months earlier, the patient had visited his GP, who, looking at the X-ray, told him his back looked just like Roman ruins. The patient, afflicted by chronic back pain, went with it. His wife called him Roman. “He became the Roman ruins,” says Professor Moseley, recalling the encounter, “but I refused to call him that because it would only add to his problem.”

The way we talk about pain affects our perception of pain. Researchers have found that reading pain descriptors such as burning, piercing or stabbing when suffering from chronic pain increases the perceived intensity of painful stimuli.

Just like breathing, pain is a physiological process and an essential, inevitable part of the human condition. Yet, it’s an inherently subjective and notoriously hard experience to convey to others, especially when it becomes chronic.

In the medical context, linguistic structures such as metaphors and similes – your knee is (like) a rusty hinge – and rhymes, like wear and tear, are widely used by patients and health professionals alike.

It’s a way of explaining something in a framework that everyone understands. “You want someone else to understand something that they currently don’t. So you find something that you both understand as a way to facilitate the new understanding,” says Professor Moseley.

Chronic pain is notoriously tricky to diagnose and treat. Clinicians often use numerical scales to assess the intensity of pain, i.e. how severe it is on a scale from 1 to 10. Linguistic descriptors are included in some diagnostic tools, such as the LANSS Pain Scale that aims to capture the pain’s quality or what it feels like (e.g. hot versus cold). The commonly used McGill Pain Questionnaire exploits 20 groups of linguistic descriptors to capture both the quality and intensity of pain experiences (e.g. hot, burning, scalding, searing, in assumed order of increasing intensity).

But several studies have highlighted how such scales and questionnaires are belittling and fail to reflect the complexity of chronic pain.

Metaphorical language can be a handy diagnostic tool as it can help communicate effectively the multidimensional nature of pain. Listening carefully to how a patient describes their pain might help recognise if they have neuropathic pain or nociceptive pain, for example. But many metaphors routinely used in the clinical setting are not only ineffective, but can also be damaging.

Take “slipped disc” for example. “It’s my favourite one to hate,” says Professor Moseley.

The phrase is now commonly used in and out of the clinic. But that wasn’t always the case. Microanatomists studying the intervertebral disc structure in the 1980s never described disc injuries as “slipped discs”. It was in the late 1980s that the phrase caught on. With CT scans becoming widely accessible, clinicians introduced the metaphor to describe what they saw on scans when looking at the spine sideways.

“It’s a very unhelpful metaphor because the shared understanding is the possibility that a disc will slip like a bar of soap,” says Professor Moseley. In reality, intervertebral discs are robust structures tightly connected to the adjacent vertebrae that cannot slip out.

Typically, pain starts as a result of an episode involving tissue damage, such as an accident, a disease or as a consequence of therapy. When pain persists long after the injuries have healed, it is less about tissue damage and more about a malfunctioning pain system. There may not be visible signs of physical damage in such cases, and investigations via X-rays and CT scans may also fail to detect an apparent cause.

Patients have to rely primarily on language to communicate their pain experience. These are the circumstances in which both patients and doctors might have more challenges in communicating, and in which patients tend to feel misunderstood and misbelieved.

When we are in pain, we tend to describe the variety of sensations we feel with metaphoric expressions that refer to bodily damage. These metaphors – stabbing pain, shooting pain – evoke weaponry and war, suggesting that pain is the enemy to fight. This is “a common and powerful metaphor we want to challenge,” says Professor Moseley.

Current pain science indicates just the contrary: pain is allied. Over the past 30 years, pain scientists have dismantled the notion that pain is a direct response to damage, i.e. the more severe an injury, the greater the pain. Instead, they have discovered that pain is a much more complex protection mechanism the brain uses to change our behaviour and avoid injuries.

All around our body, nerve cells called nociceptors detect actual or potential tissue-damaging events, such as thermal, mechanical or chemical stimuli. When one such event occurs, a nociceptor, located in that area of the body, is activated and sends a “possible threat” message to the spinal cord. Here, a spinal nociceptor takes that message up to the brain. The brain draws on a vast array of inputs – what we hear and see, our state of mind, past experience – and evaluates how dangerous the threat is.

Anything that suggests that we may be in danger will make the brain produce pain to draw our attention to the matter and protect us. Anything that means we are safe will dim the pain – anything, including words. Words are neurological events that our brain transforms into knowledge, emotions, or danger signals. Such neurological events don’t happen in isolated areas of the brain but simultaneously activate a network of brain cells, or neurotag, that lights up like a Christmas tree.

“We’re trying to get a consistent body of knowledge about pain management out into the different health professions who deal with pain.”

Professor Michael Nicholas

Some GPs may have been told that the “pain area” of the brain lights up when we hurt. But brain scan studies have shown that there is no such thing. Instead, there is a concerted activation of brain cells that fire up at the same time when the pain neurotag for that part of the body is turned on. The brain is a mass of millions, billions perhaps, of neurotags that influence each other.

Social psychologists have shown that metaphors can influence our behaviour and perception with some smelly experiments. They first recruited some volunteers and made them feel suspicious. Then, they released fish odour into the room. Those who understood the metaphor “something smells fishy” were more likely to pick up the smell.

In another experiment, they asked participants to play a financial investment game. They then released either fish odour, fart spray or water without warning. Participants were less likely to take risks in the presence of fish odour compared with fart spray or water.

“The most obvious explanation for this is that the neurotag that holds the metaphor ‘something smells fishy here’ shares brain cells with the neurotags that produced the smell of fish, or that produce the feeling of apprehension,” says Professor Moseley. And when neurotags share brain cells, they fire together.

The more that neurotags are activated, the more sensitive they become, beginning to activate with smaller cues. So for someone who has suffered from chronic knee pain for many years, hearing “your knee is like a rusty hinge” may be a strong enough trigger to activate their pain neurotag. On the contrary, the more that we clean up our language from unhelpful metaphors, the more we silence these neurotags.

Pain metaphors have been widely used throughout history. In the 18th century, the language of pain was opulent with figurative metaphors drawn from religion. The Bible provides rich narratives of suffering and metaphors of submission. Later, the emphasis shifted from submission to precisely the opposite: fighting and ultimately conquering pain. Pain was no longer an arrow flung by an infuriated deity but an invader to be battled.

Military metaphors remain ingrained in medical language today, especially when talking about cancer and chronic conditions. There is no doubt that some fight and courage may be helpful, but the ubiquitous use of war metaphors when referring to pain may do more harm than good.

Associate Professor David Butler, a physiotherapist and pain scientist at the University of South Australia and director of the NOI group has spent the past 30 years “playing with language” to help his pain-suffering patients transforming their metaphors from damaging to helpful.

In the book Explain pain supercharged, which Professor Butler has co-authored with Professor Moseley, he suggests doctors should help patients change their attitude towards their pain. So “my pain has let me down” becomes “the bruising has come out to the surface and everything is healing inside”.

“For any health professional dealing with chronic pain, learning up some formal education in the area of linguistics and transformative language is worthwhile,” he says.

Linguistic structures can help GPs convey their message more effectively so that patients leave their practice with the confidence needed to embark on the recovery journey. “The trick is to make your message more memorable, using alliteration, using anaphora, using rhyme,” Professor Butler says.

Alliterations such as “practice makes perfect”, “healthy habits” or “hormones of happiness” are well-known memory-enhancing tools, says Professor Butler. Anaphora and repetition – “it’ll stretch out your muscles, it’ll stretch out your limbs, it’ll stretch your ligaments, it’ll do great stretch” – help the patient stay focused, he says.

“Pace it, don’t race it” and “use it or lose it” are some of his favourite rhymes, says Professor Butler: “You could have been talking of the value of exercise and if a patient goes out and all they think about is ‘motion is lotion’ they’ve got a summary of it.”

Professor Butler says he would advise GPs to use diagnostic metaphors with extreme care.

Degenerative disc disease is a classic metaphorical diagnosis. “It’s a nasty metaphor that bites deeply,” says Professor Butler. “It’s got the three Ds. It’s got the alliteration. It’s got the internal rhyme of the ‘I’ inside. It’s three words, so they play off each other. It’s memorable. It’s a potent phrase that every health professional should explain and challenge,” he says.

The changes observed in the discs are nothing but a normal ageing process, the “kiss of time”, as Professor Butler calls it. It’s not degeneration, let alone a disease. “But when we tell patients that they have degenerative disc disease, they assume that it’s going to just be continuous and progressive and that there’s nothing to do about it,” says Associate Professor Michael Vagg, dean at the Faculty of Pain Medicine (ANZCA) and clinical director of Rehabilitation and Pain Services, Epworth Geelong.

Professor Vagg says doctors should carefully choose the right words to explain anatomical findings on scans clearly to patients: “It is a really difficult skill, but it’s well worth developing,” he says.

He adds that ensuring patients leave a consultation feeling heard and understood is crucial. “Listen to patients, even though that takes time,” he says. “Taking an extra 20 minutes on one particular day can save you from five appointments in the next month.”

But besides the notorious lack of time during consultations, GPs are unlikely to have received formal education on modern pain science, let alone linguistic, says Professor Vagg.

“Australia has really led the world in pain medicine,” says Associate Professor Meredith Craigie, a staff specialist in the pain management unit at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Adelaide. But the discoveries that happened in the last 30 years of pain science have too often remained out of the clinics. In most medical programs, there is not a lot of space for pain education nor for linguistics related to pain.

In 2019, Painaustralia commissioned a second edition of a report known as “The cost of pain in Australia”. The Federal Health Minister Greg Hunt launched the report and announced a $6.8 million fund for pain management strategies. Of that, $4.3 million went to the National Rural Health outreach program that aims to close the gap between metro and rural Australia. The rest of the funding supports three projects that focus on education and target both health professionals and patients.

One of these is being run by the Faculty of Pain Medicine (ANZCA) and led by Professor Craigie. “The idea is to engage with a wide range of stakeholders and put together a roadmap on which we want to work over the next 10 years to have more pain science and pain management strategies being taught in all training programs,” she says.

Professor Michael Nicholas, a clinical psychologist at the University of Sydney, is leading the second project, the Pain Education and Pain Management Program run at the Pain Management Research Institute, Sydney. The program aims to build a curriculum that can be delivered to any health professional dealing with pain management.

“We’re trying to get a consistent body of knowledge about pain management out into the different health professions who deal with pain,” says Professor Nicholas. “At the moment, they don’t have that available unless they look it up themselves individually.”

The third project, the Community Education and Awareness Program, is run by Painaustralia and aims to offer people easy access to pain management information. “This is intended to be a trusted source of quality information in one place that enables people to get informed about what’s available out there,” says Carol Bennett, CEO at Painaustralia. The program includes a range of resources and links to research studies, a discussion forum and an app where people can interact and ask questions.

Ms Bennett says the program primarily targets patients, but GPs and other health practitioners can find useful resources too, including language guidelines.

The hope is that a broader and more in-depth education in pain science across all health professionals who deal with chronic pain of any sort can lead to a shift in the language they use in their practices.

Metaphors can be convenient tools for patients and GPs to find common ground in understanding the experience of pain, but picking the right words might determine whether a patient embarks on a journey of suffering or one of recovering.

As it happened for Professor Moseley’s patient all those years ago. Ditching the Roman Ruin metaphor was the beginning of his mending.

“Last I heard from him, it was a postcard from Europe, somewhere,” says Professor Moseley. “He had just done a five-day walk, and he signed it with his real name, and then in brackets, ‘formerly Roman Ruin’.”